First published in Public History Weekly on the 31st of March 2016; https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/4-2016-11/on-the-grammars-of-school-history-who-whom/

Abstract

Grammar has a reputation for tedium, and a well-deserved one, perhaps, given the way in which was traditionally taught and the facility with which concern with grammar can become pedantry.[1] Grammar can, however, be a valuable tool for appraising historical thinking and for reflecting on how school history is made and understood.

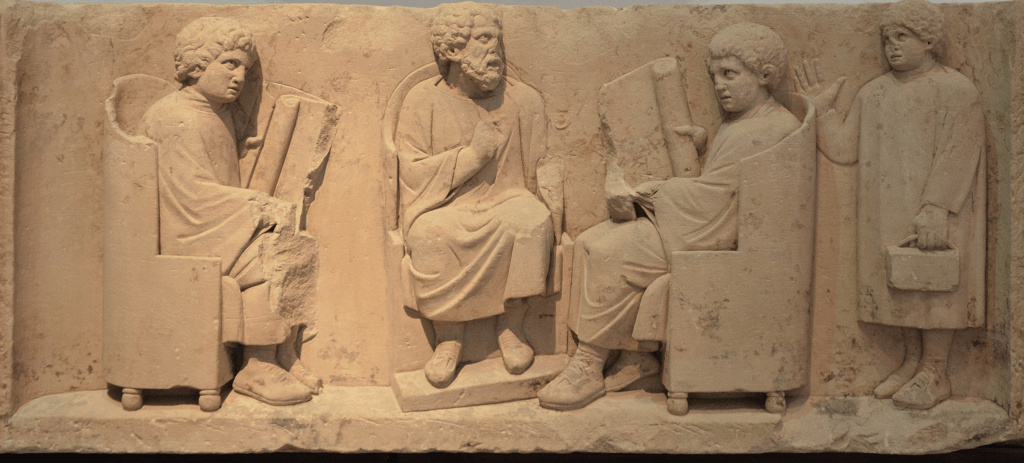

A teacher with three discipuli, around 180-185 AD, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier.

Grammar has a reputation for tedium, and a well-deserved one, perhaps, given the way in which was traditionally taught and the facility with which concern with grammar can become pedantry.[1] Grammar can, however, be a valuable tool for appraising historical thinking and for reflecting on how school history is made and understood.

Agency

Consider ‘agency’, or, in grammatical terms, the question ‘Who does what to whom?’[2] Grammatical analysis can reveal a great deal about our relationships with the past. ‘Critical historical consciousness’, for example – the historical equivalent of Nietzsche’s ‘philosophy with a hammer’ – subjects the past to the stringent scrutiny of the present, judging it iconoclastically (as with #RhodesMustFall). For ‘traditional historical consciousness’, by contrast, the past leads and ‘we’ must follow, since to live well is to reiterate ‘the best’, which exists already in the practices of ‘our’ ancestors.[3]

What is true of historical culture more generally is also true of history education: the question ‘Who whom?’ can reveal features of our learning aims for history and aspects of our students’ historical thinking that might otherwise pass unnoticed.

Case 1: The National Curriculum for History

Consider these approximately parallel passages from two iterations of the English National Curriculum for History. We need to read both documents in full, of course, to understand them but comparing these two paragraphs alone can illustrate the power of grammatical analysis.

“History fires pupils’ curiosity and imagination, moving and inspiring them with the dilemmas, choices and beliefs of people in the past. It helps pupils develop their own identities through an understanding of history at personal, local, national and international levels. It helps them to ask and answer questions of the present by engaging with the past.” (2007)[4]

“A high-quality history education will help pupils gain a coherent knowledge and understanding of Britain’s past and that of the wider world. It should inspire pupils’ curiosity to know more about the past. Teaching should equip pupils to ask perceptive questions, think critically, weigh evidence, sift arguments, and develop perspective and judgement. History helps pupils to understand the complexity of people’s lives, the process of change, the diversity of societies and relationships between different groups, as well as their own identity and the challenges of their time.” (2013)[5]

In one sense these texts are structurally identical – in both ‘history’ does things to pupils. Despite this, the contrasts are striking. In the second, history is more clearly cognitive than in the first. Pupils ‘question’, ‘think’, ‘develop… judgment’ and, in total, they control six verbs related to intellectual processes in one sentence of this passage, whereas in the first paragraph they simply ‘ask and answer questions’. In the first passage, history is presented in a more affective manner than in the second – whereas the second mentions ‘curiosity to know’, the first links curiosity to being ‘moved’ and ‘inspired’ and the agency attributed to people in the past is identified as the source of these responses.

In the first text, past people made ‘choices’, faced ‘dilemmas’ and had ‘beliefs’ but in the second the ‘lives’ of past people simply have ‘complexity’. Pupils’ identities shift in ways that may, perhaps, be pedagogically consequential between the two paragraphs. In the first, pupils actively ‘develop their own identities’ through historical study but in the second ‘their own identity’ is something that they come to ‘understand’: what was plural and pupil-generated becomes singular and, perhaps, a given.

Case 2: Students’ thinking Grammar can also reveal a lot about students’ thinking.

Consider, for example, the contrasts between these two responses by the same student to questions about historical interpretation.

“Different sources have interpretations of events and this can affect what the historian using them concludes… the social background [of the historian]… can affect interpretations… a historian with a working class background would be more inclined to favour the Chartists. The political background of the historian can affect their conclusion. A communist historian would have a very different conclusion of the Russian Revolution to a socialist.”[6]

In this text, written at start of an intervention designed to develop understandings of what historians do, the student does grant historians agency – they use sources and have conclusions; however, historians’ claims are ‘affected’ by their backgrounds or political beliefs – on this account, historians do not so much write their own texts as ventriloquize the claims of factors acting on them.

The grammar of agency is very different in this later response by the same student.

“Some historians choose to interpret sources in a more subjective light, being more critical of any inferences that can be drawn… Some historians may choose to accept the attributes of the sources… it is the interpretation of the sources that determines the conclusions which are to be drawn.”[7]

Here the historians are in charge of the verbs. They are agents of their own arguments, they make choices and it is this interpretive decision-making that ‘determines the conclusions that are to be drawn’.

We Still Believe in Grammar

Agency is only one part of the story. Grammar structures and enables historical thinking in a wide range of ways, the most obvious being time. What history could there be, after all, without the past tenses? Another example is historical explanation. Here grammar can index barriers to progression and increasing sophistication in historical thinking. Sophisticated historical explanation necessarily involves counter-factual reasoning, as Megill (2007) has argued.[8] Counter-factualism requires mastery of the conditional ( ‘if… then’ and ‘if not…. then not’) and ‘possibility thinking’, enabled by the conditional, is key to progression in historical explanation [9]

We still believe in God because we still believe in grammar, Nietzsche once quipped.[10] Whatever its negative value to the iconoclast, grammar is of positive heuristic value in history didactics. Improving historical thinking and parsing the texts that embody and express it are likely to go hand in hand. ‘Who whom?’ we might ask, when tasked with implementing or writing a curriculum proposal. ‘Who whom?’ we might ask also when thinking about what our students write and say and about how we might help them to develop more powerful historical thinking.

Further Reading

Coffin, Caroline: Historical Discourse. The language of time, cause and evaluation, London and New York 2006.

Coffin, Caroline: Learning the language of school history: the role of linguistics in mapping the writing demands of the secondary school curriculum. In: Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38 (2006) 4, pp. 413–429, http://oro.open.ac.uk/5529/ (last accessed 23.3.16).

Harris, Roy: The Linguistics of History, Edinburgh 2004.

Endnotes

[1] Butterfield, J. (2016). ‘Think you’s good at grammar? Try my seven golden rules’. The Guardian, 4th March, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/04/national-grammar-day-rules (last accessed 23.3.16).

[2] I intend ‘agency’ in both a sociological sense (denoting the power to act and make effective decisions) and a grammatical sense (where to be an agent is to be the ‘subject’ of verbs). The former is explored in Giddens, A. (1984) The Constitution of Society, Cambridge: Polity Press and the latter in Halliday, M.A.K. and Matthiessen, C.M.I.M (2014) Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar, Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

[3] Rüsen, J. (2005). History: Narration, Interpretation, Orientation. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

[4] Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (2007) History: Programme of study for key stage 3 and attainment target, London: QCA, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100202100434/http://curriculum.qcda.gov.uk/key-stages-3-and-4/subjects/key-stage-3/history/programme-of-study/index.aspx?tab=1 (last accessed 23.3.16).

[5] Department for Education (2013). History programmes of study: key stage 3 National curriculum in England, London: The Stationary Office, p. 1, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study (last accessed 23.3.16).

[6] The full text of this passage is at Chapman, A. (2012). Developing an Understanding of Historical Thinking Through Online Interaction with Academic Historians: three case studies. 2012 Yearbook of the International Society for History Didactics, 33, pp. 35-36 (last accessed 23.3.16).

[7] The full text of this passage is at ibid, p.36.

[8] Megill, A. (2007). Historical Knowledge / Historical Error: A contemporary guide to practice, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.7.

[9] Lee, P. J., & Shemilt, D. (2009). Is any explanation better than none? Over-determined narratives, senseless agencies and one-way streets in students’ learning about cause and consequence in history. Teaching History, 137, pp. 42-49.

[10] Nietzsche, F. (1889) Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with a Hammer, translated by Daniel Fidel Ferrer (2013), , https://archive.org/details/TwilightOfTheIdolsOrHowToPhilosophizeWithAHammer (last accessed 23.3.16).

Note: This post is reproduced (with a new image) from Public History Weekly. I would like to thank Publlic History Weekly for publishing it and Dr Eleni Apostoloudou for replying to my post. You can find that reply at the bottom of this page: https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/4-2016-11/on-the-grammars-of-school-history-who-whom/