The past is gone and only traces remain – relics (e.g. a special trains timetable) and reports (e.g. combat in the air reports filed by pilots after operations).

Histories are attempts to make sense of the vanished past at a later time, once the events, states of affairs, developments, people, contexts and / or institutions that histories try to make sense of have passed. Histories work with traces to generate accounts of these vanished pasts.

There are numerous varieties of history, varying on a number of dimensions, including:

- the relations to the past they assume and enact;

- the purposes that drive their constrution;

- the traditions of history-making they work within;

- the questions that they set out to answer;

- the archives and traces that they identify as relevant;

- the methods that they use to make sense of the past’s traces;

- the medium and the genres in which they are constructed;

- the audiences to whom they are addressed and by whom they are decoded and consumed;

- the moments in time in which they are written; and

- their author’s / authors’ particular contexts and characteristics.

Varieties of history include – for example – the numerous genres of academic historical writing working in the historicist tradition that we can trace back to historians like Leopold von Ranke in the early nineteenth century. Histories also include oral traditions of storytelling about the pasts, forms of public historical representation through enactment, pictorial representations of pasts, the pasts depicted or evoked through public monumental architecture, theme parks, feature films, and so on. Modern academic historical writing has been dominated by Western historical traditions – a reflection of the hegemony of Europe and American in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Nevertheless, it is not defined entirely by its origin and there are traditions of historical writing that have worked within acacemic history to challenge Eurocentric understandings, for example, the work of the Subaltern Studies Collective.

How school histories should relate to other modes of history construction is much debated. The curriulum construct ‘interpretations’ – developed in England since the early 1990s – and related concepts developed in German-speaking, Nordic and Dutch traditions of history education, such as historical ‘deconstruction,’ ‘uses of history‘ and ‘historical culture‘ – opens-up the possibility of exploring multiple genres of representing and constructing the past in history lessons, although school history often remains (and has, perhaps, recently become more) focused on recontextualising academic history for children rather than on opening-up reflection on the varieties of ways in which pasts are made present in and through contemporary culture.

There are many excellent papers in the English Professional Journal Teaching History reporting, for the most part, English history teachers’ work on interpretations in their classrooms – see here for a summary of key thinking in this tradtion (paywalled). There is relatively little systematic research on children’s thinking about historical interpretations or on history teachers’ and curriculum makers’ approaches this issue. Some findings from one tradition of research, and links to work that I have contributed on this, can be found below, as can a chapter summarising ‘interpretations’ and a link to some teaching materials on aspects of interpretation.

Research on Students’ Understandings of Historical Interpretations

Eventually, I aim to embed a comprehensive Zotero bibliography of writing on school history in this site and to include in that references to all the texts I am aware of that address interpretations, the aims of school history, causal reasoning, and so on. In the meantime, here are some links and refernces that I hope will be of interest.

Project CHATA work on interpretations (which the project called ‘accounts’) was conducted in the 1990s and was ground-breaking nationally and internationally in researchng childrens’ understandings of histories. There has been extensive work for many decades on how children think about historical evidence – for example, Denis Shemilt’s 1980 Evaluation Study of the Schools History Project – but there has been very little equivalent work on how children understand what histories are, and how children understand (or fail to understand) how historical accounts differ in kind from the traces of the past from, and with which, they are constructed. CHATA work on interpretations – which the project called ‘accounts’ – can be found in a number of places, for example:

- Lee, P. (1998) ”A lot of guess work goes on’: Children’s understanding of historical accounts,’ Teaching History, 92, pps.28-36;

- Lee, P. (2001) ‘History in an Information Culture,’ International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research, 1 (2), pp.26-43 – open access;

- Lee, P. and Shemilt, D. (2004) ‘I just wish we could go back in the past and find out what really happened’: progression in understanding about historical accounts,’ Teaching History, 117, pps.25-31; and

- Lee, P. (2005) ‘Putting Principles into Practice: Understanding History,’ in M. Suzanne Donovan and John D. Bransford (eds.) How Students Learn: History in the Classroom, Washington: The National Academies Press, pp.31-77 (pages 59-61 deal with accounts) – open access.

Twenty years ago, I worked on an EdD on children’s understandings of historical interpretations under the supervision of Peter Lee, at what was then the Institute of Education, University of London. My work built very directly on Project CHATA approaches and research instruments, but worked with older students’ understandings (16-19-year-old students). Like much work on interpretations to date, my research focused exclusively on understandings of academic historical accounts. My EdD Thesis can be downloaded at the link below as can three papers discussing some of these findings:

- Chapman, A. (2009) Towards an Interpretations Heuristic: A case study exploration of 16-19-year-old students’ ideas about explaining variation in historical accounts. EdD Thesis: Institute of Education, University of London.

- Chapman, A. (2011) ‘Understanding Historical Knowing: Evidence and Accounts.’ In Lukas Perikleous and Denis Shemilt (eds.) The Future of the Past: Why History Education Matters. Nicosia: AHDR, pp.170-214; and

- Chapman, A. (2014) ‘Using Jörn Rüsen’s ‘disciplinary matrix’ to develop understandings of historical interpretation.’ Caderno de Pesquisa: Pensamento Educacional, 9 (21): 67-85

- Chapman, A and Georgiou, M. (2021) ‘Powerful knowledge building and conceptual change research: Learning from research on ‘historical accounts’ in England and Cyprus.‘ In Arthur Chapman (ed.) Knowing History in Schools: Powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge. London: UCL Press, pp. 72-96.

Whilst completing my thesis, I worked on a number of Higher Education Academy funded projects on historical interpretations. There were three iterations of this work – a 2007/8 project involving one school, one college and two academic historians, a 2009 iteration involving three colleges and two academic historians and a 2011/12 iteration involving five schools and four colleges and six academic historians. In all cases, the projects worked through discussion board platforms bringing students in different institutions into dialogue with each other and into dialogue with academic historians. The projects aimed to see if this dialogue could result in discernable progression in students’ thining. Two History Virtual Academy project reports, describing the processes involved and analysing student outcomes, can be accessed at the links below:

- Chapman, A. (2009) Supporting High Achievement and Transition to Higher Education Through History Virtual Academies, Teaching Development Grant Round 5 Final Report. Liverpool: Higher Education Academy; and

- Chapman, A., Elliott, G. and Poole, R. (2012) The History Virtual Academy Project: Facilitating inter and intra-sector dialogue and knowledge transfer through online collaboration. Warwick: The History Subject Centre.

The project reports were preliminary and written to tight deadlines. Papers exploring some of the findings from the HVA project more systematically can be found at the links that follow (all but the third can be downloaded at the links):

- Chapman, A. (2011) Chapman, A. (2011) ‘Twist and shout? Developing sixth-form students’ thinking about historical interpretation‘, Teaching History 142, pp.24-32;

- Chapman, A. (2012) ‘‘They’ have come to differing opinions because of their differing interpretations: Developing 16-19 year-old English Students’ Understandings of Historical Interpretation through On-line Inter-institutional Discussion.’ International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research, 11 (1), pp.188-214;

- Chapman, A. and Goldsmith, E. (2015) ‘Dialoge Between the Source and the Historian’s Ciew Occurs: Mapping change in student thinking about historical accounts in expert and peer online discussion.’ In Arthur Chapman, Arie Wilschut (eds.), Joined-up History: New Directions in History Education Research. Charlottesville, CA: Information Age Publishing.

- Chapman, A. (2022) ”Because They Measure Success Differently’: Building students’ understandings of how historical accounts are made – possibility and potential,’ Revista Territórios e Fronteiras 14(2); 21-37.

The following book chapter works through some of the design principles for discussion arising through the History Virtual Academy , and also explores ideas about developing historical argument that may be of more general interest (the link is to a download of the pre-publication proof of the chapter):

- Chapman, A. (2013) ‘Using discussion forums to support historical learning,’ In Terry Hadyn (ed.) Using New Technologies to Enhance Teaching and Learning in History, London and New York: Routledge, pps.58-72.

Overviewing Historical Interpretations

In 2010, I wrote a chapter on interpretations for Ian Davies’ edited collection Debates in History Teaching, which was re-published in a slightly revised form in the 2017 second edition of that book. The chapter explores what is distinctive about historical intepretations and makes some suggestions on teaching approaches. You can download the 2016 pre-publication final proof of that chapter at the link below:

- Chapman, A. (2017) ‘Historical Interpretations’ in Ian Davies (ed.) Debates in History Teaching, London and New York: Routledge, pp.96-108.

Teaching Strategies and Approaches

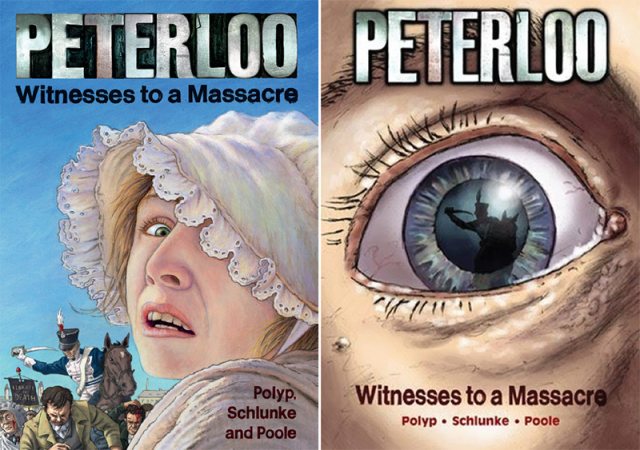

Draft (left) and final covers for Peterloo: Witness to A Massacre, 2019

In 2016 I worked on a guide for teachers on teaching about historical interpretations for Pearsons / Edexcel. There are two versions of this guide and only the first ‘abriged’ version has official status. The second link below is to an earlier ‘full’ version of this guide which expresses my thinking only.

- Chapman, A. (2016) Developing Students’ Understanding of Historical Interpretations (abridged version). Oxford: Pearsons; and

- Chapman, A. (2016) Developing Students’ Understanding of Historical Interpretations. Oxford: Pearsons.

In 2019 and 2020, Jen Turner and I worked on some teaching materials exploring narrative aspects of historical interpretations in the context of Peterloo. We focused, in particular, on key decisions that historians needs must make when constructing an historical narrative. We foucsed our thinking on this through the Peterloo graphic novel, created collaboratively by graphic artists and a historian, and we incorporated the open access schools’ version of the graphic novel and interviews with the makers of the original graphic novel into the materials. You can read about this on the blog site link below which takes you to a link where you can download the schools version of the graphic novel, the rationale document and lesson plans and the lesson materials that Jen Turner and I created.

- London HiESIG (2019) Interpreting Peterloo. London: History in Education Special Interest Group.

Jen and I collected classroom data evaluating the sequence of lessons in summer 2022. We hace recently published an article in the Historical Association’s professional journal Teaching History reporting the scheme of work design and providing some initial analysis. We are currently working on a more systematic analysis of the data for a peer-reviewed journal.

- Turner, J. and Chapman, A. (2023) ‘It does duty for any amount of mayhem’: helping Year 8 to understand historians’ narrative decision-making,’ Teaching History, 190, pp.80-91.

In 2020, I was invited to contribute two workshops on historical linterpretations by the Be Bold History Network on teaching historicall intepretations. You can access recordings of these two sessions at the links below:

- Chapman, A. (2020) Teaching Interpretations, Part 1. London: Be Bold History Network.

- Chapman, A. (2020) Teaching Interpretations, Part 2. London: Be Bold History Network.

Page last edited: 14th May 2023