Introduction

This is the second in a series of posts about ‘narrative ethics’ in history education. The first post in the series can be found here.

This post is concerned, largely, with laying the ground-work for a discussion of Kurt Vonnegut’s work on the shape of stories in the third blog in this series. This post aims to set-up some concepts from schema theory.

Like many of my colleagues in history education in England, I am an amateur and a magpie of schema theory rather than an expert exponent of it. All I do here is bring together some ideas that I’ve found interesting and that, it seems to me, might be useful to history educators.

These ideas seem to converge to a degree – specifically, aspects of the work of David Bordwell and James Wertsch – and also to take us beyond the somewhat undifferentiated ways in which schema have often been discussed in history education in England in the last ten years or so, often drawing on Chapter 2 of Hirsch’s Cultural Literacy, 1987.

I am sure that there’s much more to say than I manage to say here: this is just a start.

Constructing Story: Assumption Prediction, Confirmation, Revision

Cognitive scientific explanations of narrative comprehension, David Bordwell has argued in various places (Bordwell, 1985 & 2009), can fruitfully make use of the notions of schemata and of prediction to make sense of how we interpret or construct stories.

We interpret incoming data (in a film, text, sound or other narrative context), the story goes, by forming hypotheses about the larger patterns that these data are part of, and these hypotheses are then confirmed or revised, as we continue to make sense of new data and as the narrative continues to unfold.

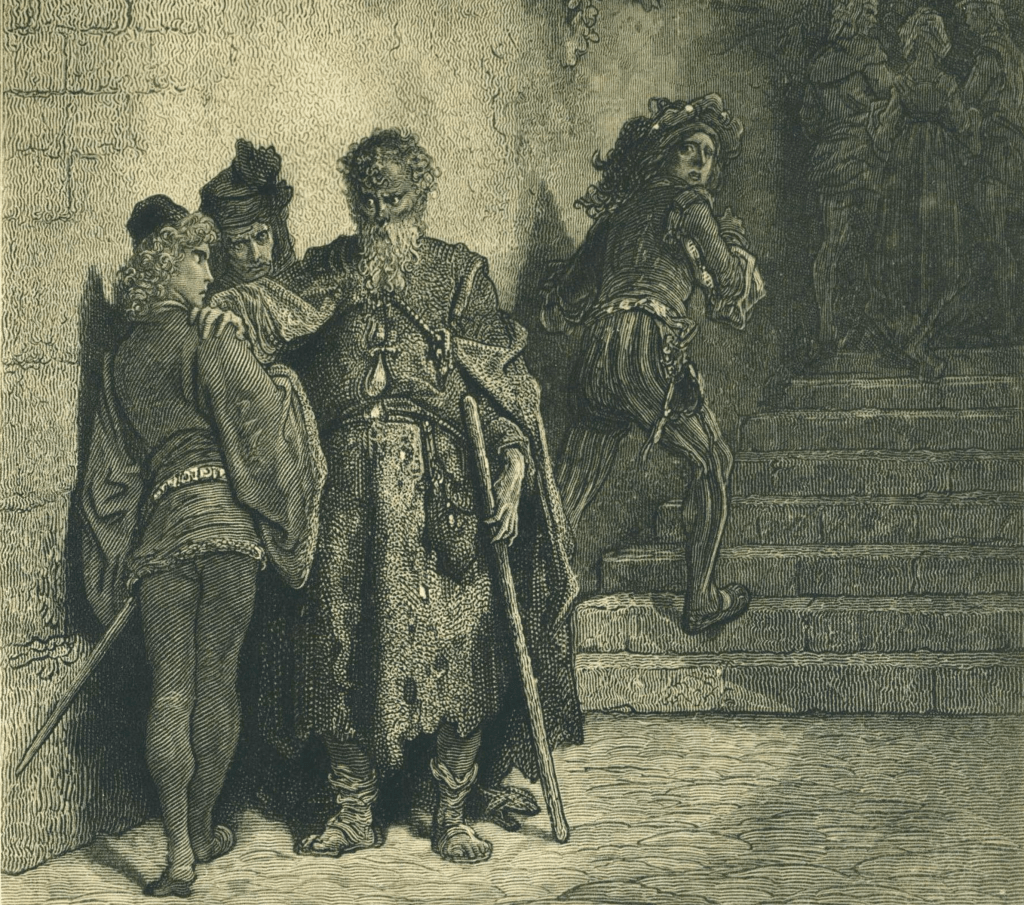

The hypotheses story-consumers make could include the hypothesis that we are experiencing a story (rather than just random unnconnected data). They could include the hypothesis that the story we are experiencing is a story of a particular type (e.g., a pirate story). They could include the hyptheses that X is the pro- (e.g., Little Red Riding Hood) and that Y is the antagonist (e.g., the Wolf) in the story. They could also include the hypothesis that the events we are viewing constitute a larger whole (e.g., a chase sequence), and the hypothesis that this chase is part of a larger story sequence (e.g., a quest narrative). And so on, and so on.

On this model, the consumer of stories co-constructs the narrative they are experiening by forming hypotheses about what is going on and by bringing together and organising the narrative data presented to them (in a book, film, conversation over coffee, etc.). They are co-constructing because, in most cases, someone else is also contributing (the film-maker, the novelist, and so on), and because author and consumer participate in shared conventions of meaning, and share many of the same schemata.

The consumer (or co-constructor) of stories brings together and organises this incoming story-data using their pre-existing cultural resources (i.e., knowledge of conventions about story operative in their culture and context). They use their knowledge to organise incoming data into patterns that enable them to construct an ongoing story that has a pattern they recognise. The story consumer/constructor then confirms or revises these hypthesis about what is going on in the light of incoming narrative data. This process of pattern and sense making is largely unconscious / unreflective – unless, of course, incoming data cannot easily be construed using available resources, and conscious thought and sense-making is then required.

The conventions and assumptions that readers draw upon are typically also shared by story-makers, which allows for largely shared meanings to be conveyed in particular narrative cultures. However, this commonality of assumptions begins to dissolve when consumers are presented with stories from a different cultural time or different cultural space, where story-co-constructors share different conventions. This point is well-illustrated in the ‘War of the Ghosts’ experiment, described in Frederic Bartlett’s Remembering (1932), perhaps the most influential book in the history of schema theory – a study in which Bartlett asked middle class English subjects to re-tell a Chinook narrative, a process in which the English re-tellers re-wrote and misconstrued the Chinook story to fit with their conventional expectations, without consciously setting out to do so.

Constructing Story: Templates and Protoypes

This ongoing process of assumption, prediction and confirmation / revison works by deploying culturally-learned and conventional schemata of various kinds. These schemata are cookie-cutter-like models of the shapes that things in story worlds usually conform to. Schemata model the kinds or genres of story that we can expect to find (e.g., horror stories, ‘Westerns,’ etc.). Schemata model what plots look like in different story-types; and they model the typical scences and locales we might expect to find in particular story-worlds. They also model things like the typical equipment, actions and interactions that might be found in story locales, and the kinds of actor or agents we might expect to find there. They also model roles agents might plany in story-worlds and the kinds of motivation they might have. And so on, and so on.

Bordwell (1985: pp.29-47) divides these schemata into ‘template’ schemata (for plots and developments in time) and ‘prototype’ schemata (for character types, for mise en scène, etc). The difference between the two types of schemata can be grasped, it seems to me, using the example of Cluedo (or Clue in the US), a board game patented in the UK in 1944 and first produced in 1949 and still in play today, albeit in updated forms.

Cluedo is a ‘country house murder’ game and was itself based on ‘country house murder mystery weekends,’ which were in turn based on the typical conventions (templates and prototypes) developed in the ‘murder mystery novel,’ (works such as Agatha Christie’s The Body In The Library, 1942). We can see, then, how Cluedo is an abstraction from an abstraction of a genre in which reality itself has been modelled in a highly stylised way. Cluedo takes the templates and protoypes of a genre, then, and stereotypes a stereotype based on them.

Cluedo‘s narrative templates are simple – one of the upper class guests in the ‘country house’ setting is always murdered by one of the others; the identity of that murderer has been concealed; and game unfolds using the classic ‘murder mystery’ narrative template of investigatoin and interrogation of suspect individuals by detectives, culminating in a summons of all the country house’s inhabitants to ‘the Library’ where the truth is to be revealed (a template drawn upon time after time in Agatha Christie murder mystery stories).

The prototypes in play in the game include prototypes for locale / mise en scène (country house, with dining room, ball room, library, etc.), artefacts (the lead piping, the rope, and other murder weapons), and pro/ant-agonists (Miss Scarlett, Professor Plumb, Colonel Mustard, etc).

Students as Active Meaning-makers

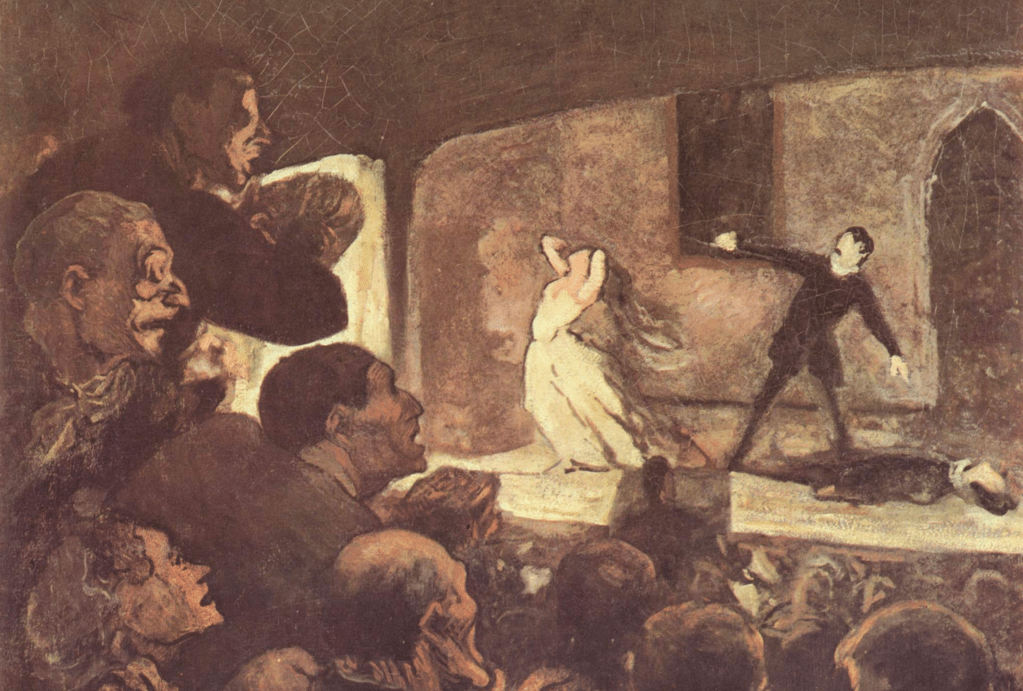

The constructivist account of story-comprehension as story-co-construction is one in which the story-consumer (viewer, listener, etc) is highly active. They make and revise hypotheses as they consume, drawing on available cultural resources (schemata) to make sense of data they are presented with on TV or cinema screen, through what they hear, through what they read, through the images they are presented with (and so on). These resources are learned, culture-specific and they change over time.

My hypothesis, in what follows, is that what is true of making sense of ‘fictional’ stories (Bordwell’s focus) is as true of making sense of ‘factual’ stories also, such as the stories we focus on in history lessons.

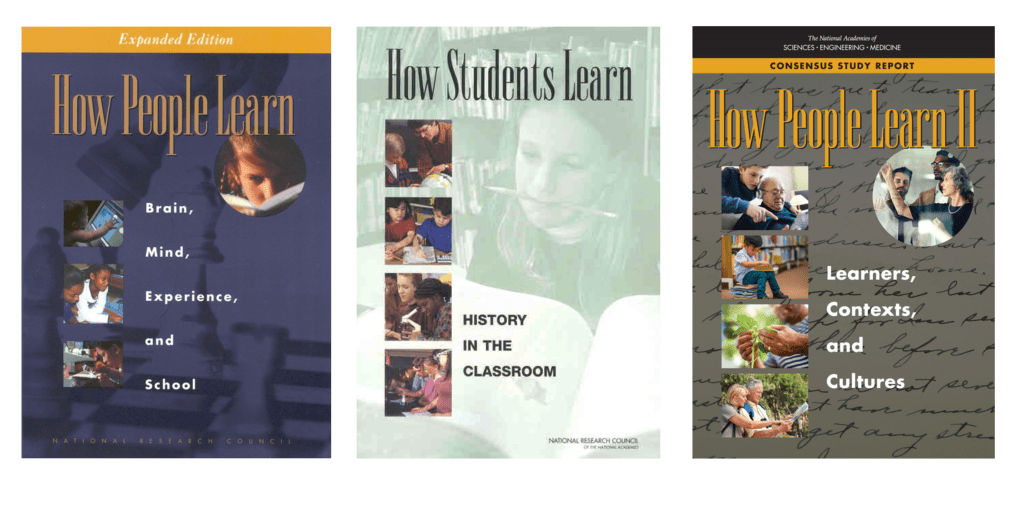

If we accept that premis then in follows that teachers need to attend to the cultural resources that students bring to the task of making sense of the stories we present them with in history. They will, as the How People Learn project showed more generally, bring their own assumptions to the task of story-construction and these will draw upon their own prior experience of the world and their experience of how stories about the world work.

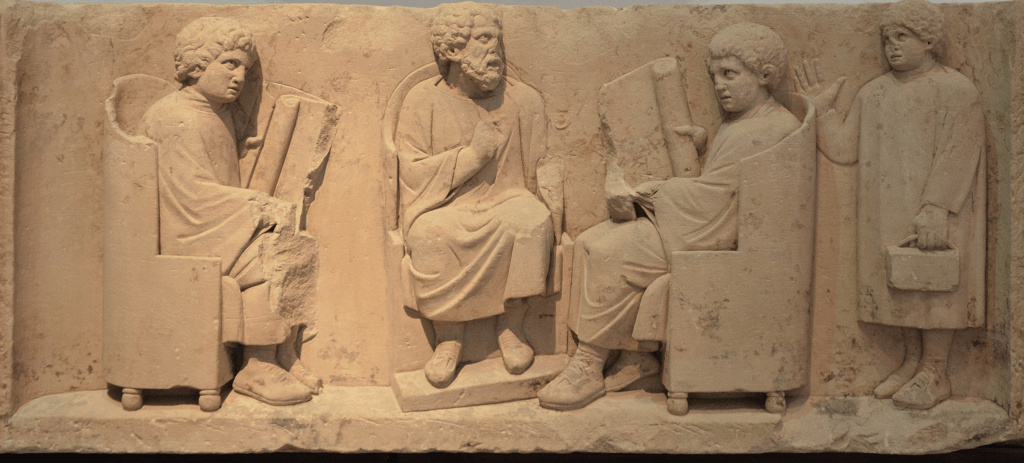

As all historians know, context is everything in history, and the worlds of the past differ from the worlds of the present in fundamental ways – which is one reason why, of course, the concept ‘anachronism’ is of such interest to history educators. Helping children make sense of stories about the past involves developing and expanding the prior resources they bring to the task of constructing meaning. It means building new prototypes (e.g., for the kinds of actors, beliefs and motivations that one might find in medieval contexts; e.g., for those one might find amongst the Victorian Middle Classes; e.g., those we might find amongst Aztec nobility and amongst Spanish Conquistadores). It means building new templates of how events can unfold (What happens in a revolution, and uprising, and so on?), including understandings of what narrative lines of development might look like in history, as opposed to other genres of story-making.

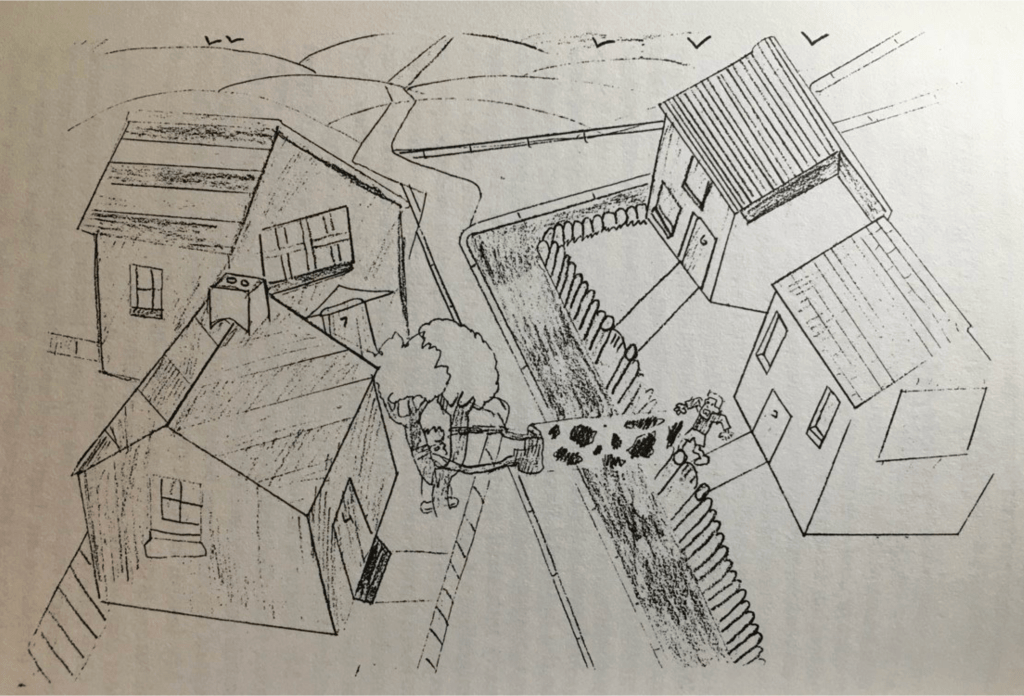

It is also likely to involve ‘clearing the ground’ and trying to help deconstruct misconceptions that students may have, such, for example, as the misconceptions of what 18th Century Paris looked like and of how terror operated that seem to be in play in the mind of the student who drew the following representation of the French Revolutionary Terror.

Narrative comprehension and text comprehension

We have become much more used than we ever were, in educational practice in the last 15 years or so, to cognitive science and cognitive scientific paradigms and research. I would no longer be told now, as I was about 15 years ago, to avoid using the word ‘cognitive’ in an article for a teacher magazine because it would put teachers off reading it. There are limitations. nevertheless, it seems to me, in how cogntive science has been appropriated, in England, and, also, in the use made of schema theory in history education literature.

Talk about schema and schemata has increased significantly in history education discourse in England since the early 2010s, however, it seems to me to be quite limited to understandings of specific substantive concepts and to draw on work on text-comprehension at the level of the sentence or paragraph. It also often draws quite heavily on a limited range of references (as I have noted above, Chapter 2 of Hirsch’s Cultural Literacy is often a key reference – we need more).

Understanding a story involves more than understanding a sentence or a paragraph and we need a wider repertoire of schema-types than is typically found in text comprehension work. Hence, it seems to me, the suggestiveness of Bordwell’s typology (prototype and template schemata), although differentiating a concept into to two subtypes is only a beginning and not an end.

Schema have also been discussed in the work of James Wertsch (see, for example, Wertsch 1998, 2002 and 2021), and in the work of researchers drawing on his example (for example, see Wertsch’s introduction and the related empirical papers in this open acces journal special edition on nations and narrations). Wertsch’s work couldn’t be more different from text-comprehension appropriation of schema-theory – it works at the very zoomed-out and large scale of the tools cultures use to make sense of themselves, and not at the micro-level of understanding X, Y or Z text.

Wertsch distinguishes between specific narratives and schematic narrative templates – the former are particular stories about specific events (e.g., the story of the evacuation of troops from the beaches of Dunkirk in late May and early June 1940) and the latter are large-scale interpretive stories that different cultures use (Wertcsh hypothesises) to construct large scale narratives about themselves and that they also use to help make sense of particular events that arise.

Much of Wertsch’s work on narrative templates works through data sets about narratives in the former Soviet Union and its former Eastern Bloc satelites. One of the conclusions that Wertsch draws is that Russian narrative identity, at a national level, is bound-up with, and expressed through, a ‘trimuph over alien forces’ narrative template, in which Mother Russia is invaded (without provocation and without good reason) by an external aggressor, and then almost defeated at great cost in life and treasure at the hands of this nefarious foe, before, finally and through great sacrifice, expelling the invader and restoring her former position. The point about such templates, Wertsh argues, is that they are identity-stabilising large-scale stories that members of national cultures can reach for, effortlessly and without much thought, at moments of crisis, and use and re-use over time. Whether or not using any particular template would be a positive thing, overall, in terms of the actions and reactions a template might sanction, is, of course, another matter.

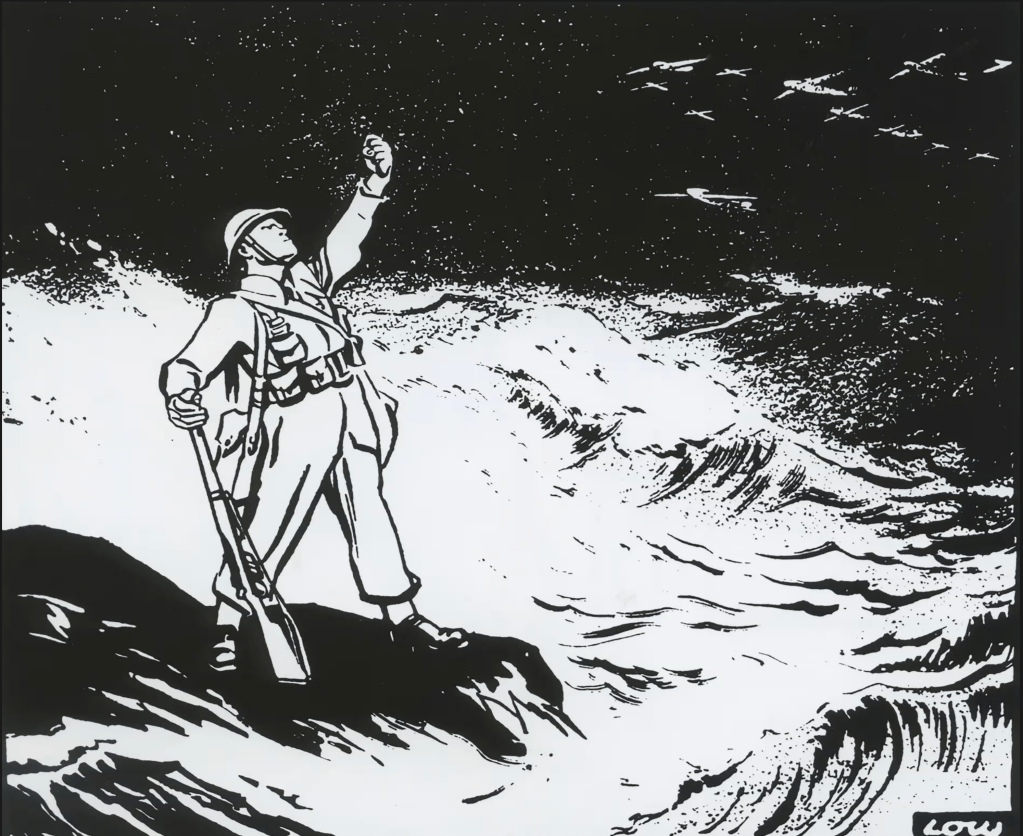

An equivalent in Britain is captured in David Low’s famous cartoon (above) which, one might say, both encodes and deploys a story the British are fond of telling themselves about their resilience and their ability to muddle through and resist overwhelming odds through sheer grit – a schematic narrative template that is periodically refunctioned, for example, in the dramatic re-emergence of the ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster.

This poster, now treated almost as a pure embodiment and expression of the ‘Blitz Spirit,’ was created in 1939 but shelved before use in 1940, and re-emerged around 2000, before becaming almost ubiquitous during the austerity years after 2010. A poster rejected in 1939/40, then, became a cultural archetype of the spirit of 1940, and a way of reasserting another questionable narrative – Britain was not alone in 1940, she had ‘her’ Empire with her. A questionable narrative that might, at times, do as much harm as good.

A useful project, it seems to me, might be to take Bordwell’s typology (prototypes and templates) and to seek to differentiate it further, thus generating a model of the range of schemata and resources that we might aim to try and develop in our students to help them make sense of the stories about the past that we want them to be able to master, understand, and use.

It seems to me, also, that Wertsch’s work might be useful in this endeavour. I find the notion of culture-wide shared narratives a little dizzying (‘How might we know what they are and that they exist (if they do)?’ is one question, and there are others). It seems sensible to explore what Philpott called ‘meso-level’ uses of Wertsch’s ideas (1), however, and to explore the possibility that culturally constructed conventionalised narrative schemata exist and work at varying levels of complexity, forming a spectrum between micro-stories (such as the Dunkirk story about little boats) and Wertch’s macro-level templates.

From Prototypes to Stereotypes: Affordances and Constraints

Cluedo is a highly limited representation of the world – and one that, one imagines, no one takes seriously. Arguably, however, we should take world-building representations, in all their forms, very seriously, as they all contribute to the overall task of making our life-worlds and delineating their possibilities and exclusions, to one degree or another. All stories matter, on this understanding, in the sense that they all contribute, even if only in a very small way in an individual case, to consituting world-pictures, social norms and paradigms, and, thus, to shaping and delimiting future possibilities – an awareness that has underwritten much contestation in cultural politics in the last fifty years.

The history of the worlds represented in Cluedo over time demonstrates this. The world represented in the original Cluedo, was prototypically White and prototypically patriarchal: all the characters in the game play were White and whereas all the male characters were identified by their roles in society (Colonel Mustard, Professor Plumb, Reverend Green) two of the three female characters were identified solely by their marital status (Mrs Peacock, Miss Scarlet). The 2023 edition of Clue, by contrast, features an African-American Miss Scarlett and an an African-American Professor Plumb, and although Miss Scarlett is sexualised in appearance (the ‘scarlet woman’ stereotype persists, perhaps one might say) the game notes tell us she’s in fact a ‘sharply intelligent investigative journalist’ masquerading as a ‘socialite.’ Furthermore, the remaining two female characters are now identified by their role (Mrs Peacock becoming Solicitor Peacock, and Mrs White, always visually a chef, being renamed to become Chef White). Despite these changes the game continues to have a social bias. It is still largely about the rich and powerful and, although from the perspective of Brecht’s Worker it improves upon high political history by including a cook – a fact that acknowledges pointing the existence of a workers enabling all this ‘luxury’ – there is no possibility in the game play for the largely invisible working classes to organise and contest the inequalities that the game’s mise en scène simply takes for granted.

World representations like Cluedo matter, perhaps, in a number of other ways, also, not least by pointing to historical processes that have contributed to the shaping of ideas of taste, wealth and status in the United Kingdom, and more broadly, to cultivating a romanticised Downton Abbey paradigm of Englishness.

In addition to being a culturally available prototype, the ‘country house’ is also a historical symbol or synecdoche of a much larger and much more brutal history. As critics of the ‘Jane Austen’ world of Regency ‘elegance’ have frequently pointed out, and as projects like Corinne Fowler’s Colonial Countryside Project have shown, the wealth that built these expressions of power and conspicuous consumption, and that enabled this ‘elegance,’ had its roots in enslavement, empire and other forms of imperial extraction and exploitation. A fact that is very dramatically apparent, for example, in cases like Powys Castle and Harewood House.

Do the world-representations provided in history classes present a limited picture of past worlds and help to perpetuate notions of status and power created in deeply unequal class-, gender- and race-divided societies? Do we, alternatively, develop rounded pictures of past realities that explore the dynamics of how those social, cultural, economic and political formations worked, for example, to create, control and selectively distribute wealth, status, power and life-chances? Are the prototypical images of actors in the past that we present ones that say that only upper class men had agency and could shape their worlds, or do the stories we tell and co-construct in class show, alternatively, the ways in which the actions and counter-actions of all members of past societies came, in interaction with each other, to shape and reshape past worlds, and to help to create our worlds?

Do do the protypes of past actors, states of affairs and processes that history education helps to build sanitise the past – like the sheen on well-polished Gillow furniture that osbcures any connections with enslaved mahogany loggers and processors? Or, like Lubaina Himid’s Lancaster Dinner Serivce, commissioned for the bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade, do our history lessons give voice to and make present both past systems of power and exploitation and the agency of those who challenged the inequalities underpinning them?

Narrative Ethics and Historical Relevance

The importance of these questions, and the differences that narratively inclusive history teaching can make, are pointed to by some largely-undiscussed findings of one of the most significant history education research studies conducted in the twentieth century – Denis Shemilt’s evaluation study of the Schools Council History13-16, itself one of the most important curriculum development projects that we have seen in history education to date.

Shemilt’s study compared outcomes for children taught conventional political history (the ‘control pupils’) and for children taught history in the innovative manner developed by the SCHP (now the SHP), a project with innovative pedagogy that also aimed to change the content-focus of school history so that it foregrounded ‘ordinary people,’ and social and economic history.

Although Shemilt was too careful a researcher to overclaim and only present positive findings about the differences between ‘control’ and ‘Project pupils,’ he nevertheless reported some highly suggestive differences in attitudes towards history and in the sense of personal agency expressed by pupils in the two groups.

On the one, hand, ‘most History 13-16 candidates’ found ‘the subject personally relevant… because they see it as dealing with people like themselves (Shemilt, 1980: p.23). On the other hand:

A narrative-ethical question that arises from these considerations, I think, is the following: ‘Does our history curriculum develop prototypes of past actors that help students feel empowered and see their everday lives – and the lives of ordinary people in the past – as ‘the fabric upon which the remarkable and spectacular’ can be ‘woven?’ Altneratively, does it create a vision of the world (past and future) in which only powerful minorities have agency and in which only powerful minorities have a world to make and shape?’

Shemilt’s findings suggest that attending to these matters can have significant impacts on learners and on the prototypes and world-models their history lessons can help them build.

Conclusion

This post has tried to show that the notion of prototype schemata might have some value in helping history educators think critically about inclusivity and the implications of their curriculum choices, and of the narratives that they tell, for children’s sense of agency and self.

It has also, I hope, prepated the ground for reflection of the possible value for history educators of Kurt Vonnegut’s work on story templates, or what he calls the ‘shape of stories.’

*****

Endnotes

(1) I would like to dedicate my work on narrative ethics to the memory of Professor Carey Philpott who died suddently and much too young in January 2017. We had started to do some work together on narrative in educational policy in the run up to the BERA conference that September in Leeds and it is a matter of great regret to me that we could not continue that work together for many more years.