Introduction

This is the third in a series of posts about ‘narrative ethics’ in history education. The first and second posts in the series can be found here and here.

This and the posts that follow in this series focus on aspects of the work of Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), an American novelist and an exponent of historiographic metafiction.

Vonnegut was an infantry scout in World War II and was captured, shortly after being first deployed, in the Battle of the Bulge. As a prisoner of war he experienced the British and American bombing of Dresden. He survived the firestorm, ironically, because he was accommodated in a slaughterhouse, which had a particularly deep cellar designed to keep animal carcases cool. He was subsequently involved in the clean-up of the bomb dammage and the disposal of the bodies of victims – an activity that he mordantly described as corpse-mining (Mother Night, 1966, page viii)

Being saved by sheltering in a slaughterhouse is, of course, a deeply ironic circumstance – killing, not saving, is what a slaughterhouse is for. Unsurprisingly, Vonnegut was a deeply ironic writer. Although he writes about the past in Slaughterhouse 5, he does so metafictionally, foregrounding and questioning the means available to a writer for representing reality and atrocity.

Although he diminished the impact of his experiences in Dresden on his writing career, the bombing of Dresden was the focus for his most famous and most successful novel, Slaughterhouse 5 (1969), and it shaped aspects of his other novels (notably Mother Night, 1966). He returned to the topic of Dresden again and again throughout his career, and his experiences undoubtedly played a role in shaping his broader anti-war outlook, expressed, for example in his last book, A Man Without a Country: A Memoir of Life in George W. Bush’s America (2005). It has been suggested – altough one might be sceptical of psychological explanations for textual phenomena – that his style of narration and the substance of the fictional worlds that Vonnegut created suggest he suffered from PTSD as a result of his wartime experiences.

Vonnegut’s reflections, in Slaughterhouse 5, on the dangers of stories that can make our heads ‘echo with balderdash’ (Vonnegut, 1965: 55) and give warrant to actions that cause massacres, will be the subject of the next blog in this series. I am going to focus, here, on Vonnegut’s work on the ‘shape of stories’ and on his questioning of what he saw as the simplistic and delusional story-patterns underlying much of ‘our’ narrative tradition. This aspect of Vonnegut’s work centres on the sceptical interrogation of plot and emplotment, something I interpret as aligning with work on narrative templates (discussed in the previous blog in this series).

My contention, here, is that cultivating reflection on emplotment, so that students become sensitive to and aware of how it can be used and abused in history-stories, is likely to be a useful activity for history educators to engage in; and that a disposition of incredulity towards certain types of narrative (to borrow a phrase of Jean-François Lyotard‘s from The Postmodern Condition) is something that history education should seek to develop in students.

Narrative Templates and the Shapes of Stories

Although Vonnegut was a prolific author of novels, short stories, plays and commencement addresses, he wasn’t much of a finisher where academic study was concerned. He started, but never finished, a science degree and Cornell before enlisting as an infantry private in January 1943, and he struggled to finish his Master’s degree in Anthropology at the University of Chicago after World War II – a course of study he followed after demobilisation in 1945, benefitting from a GI Bill scholarship. He submitted and had his dissertation rejected in 1947 and then, again, in 1965, before Chicago awarded him an honorary degree, accepting his novel Cat’s Cradle (1963) as a thesis in 1971.

The version of his thesis rejected in 1965, entitled Fluctuations Between Good and Ill Fortune in Simple Tales, was put to frequent subsequent use by Vonnegut, in his teaching at the University of Iowa ‘Writers Workshop’ in 1965/6 and 1966/7, and subsequently, in numerous talks, many of which are now available online and also in the largely autobiographical Palm Sunday (1981) and A Man Without A Country (2005).(1)

As is often the case with Vonnegut, it is hard to tell how seriously he wants us to take what he says – he usually presented his ideas about story with characteristic humour and self-deprecation. Sometimes, he presents his models as tools to help a hack-writer make money – ‘plots’ become ‘ways to keep readers reading’ (Vonnegut and McConnell, 2019: 202). At other times he presents his work on story as an anthropological inquiry for which ‘the shape of a given socieity’s stories is at least as interesting as the shape of its pots or spreadheads’ (Vonnegut, 1981: 312).

What he purports to be analysing shifts, also. In Palm Sunday, he describes himself as collecting and analysing ‘popular stories from fantastically various societies’ (1981: 312), but in ‘Here’s a Lesson in Creative Writing’ (Vonnegut, 2005: 23-45) he implies that these analyses only map the literature of limited range of cultures and that his focus is contemporary American popular literature (2).

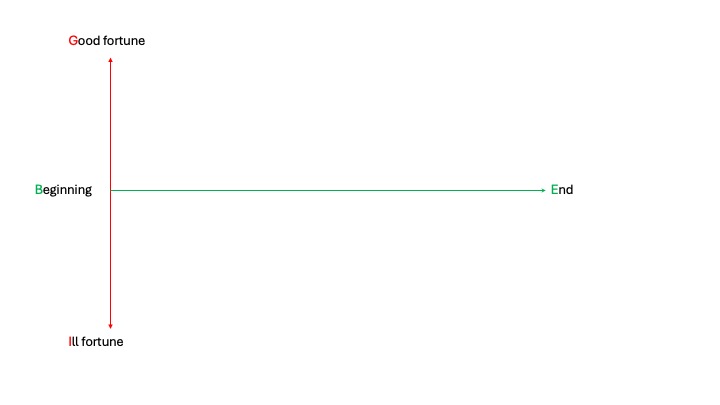

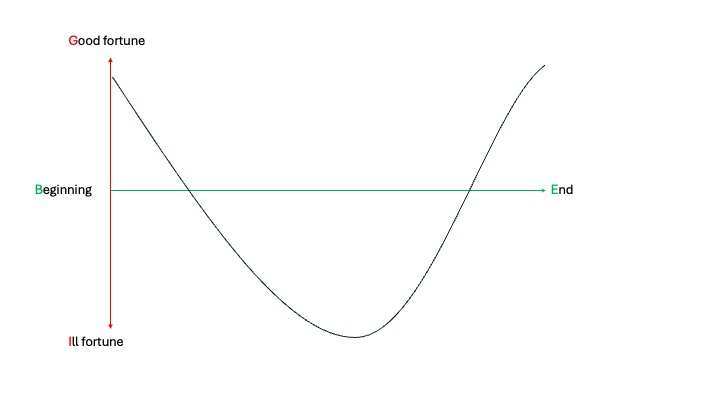

The fundamental idea behind Vonnegut’s story schemata is ‘that stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper’ (Vonnegut, 1981: 312), usign a schema that posits a ‘G-I axis: good fortune – ill fortune,’ and a ‘B-E axis’ on which ‘B’ is for ‘beginning’ (Vonnegut, 2005: 15) and ‘E stands for end’ (Vonnegut, 1981: 313), as in the figures above and below. The top of the GI axis represents ‘great prosperity’ and ‘wonderful health,’ the bottom ‘death… terrible poverty’ and ‘sickness,’ and the middle (where the BE line sits) represents the ‘average state of affairs’ (Vonnegut, 2005: 25). As Vonnegut summarised things in 1981: ‘The late Nelson Rockerfeller, for example, would be very close to the top of the G-I scale on his wedding day. A shopping-bag lady waking up on a doorstep this morning would be somewhere nearer the middle, but not at the bottom, since the day is balmy and clear’ (Vonnegut, 1981: 313).

Graphing the fortunes of the entity whose story you are mapping over time (B-E) on the ‘good-ill fortune’ scale (G-I) gives you the shape of that entity’s story, in terms of improvement and decline against the relevant societal average over time.

Vonnegut’s 1965 dissertation listed 17 story shapes in an appendix, six are presented in Palm Sunday (1981) and five in A Man Without A Country (2005). Maya Ailam has created 8 remarkable graphics that interpret Vonnegut’s shapes (available here).

The diagram above replicates what Vonnegut calls the ‘man in a hole’ schema. For the man, things begin well but this equilibrium is disrupted by events that dramatically worsen his position until he reaches the bottom of the ‘hole’ into which ill-fortune has pitched him. The man does not give-up, however, but, through a struggle against outrageous fortune, he opposes and overcomes his troubles and climbs back out of the whole, returning to the position he started in, or to a position slightly better than his starting position.

In addition to the ‘man in hole’ schema, Vonnegut discusses a number of other schemata, including ‘boy meets girl,’ ‘Cinderella,’ and ‘Kafka’ (Vonnegut 1981: 312-315).

Applications in History Education and Historical Theory

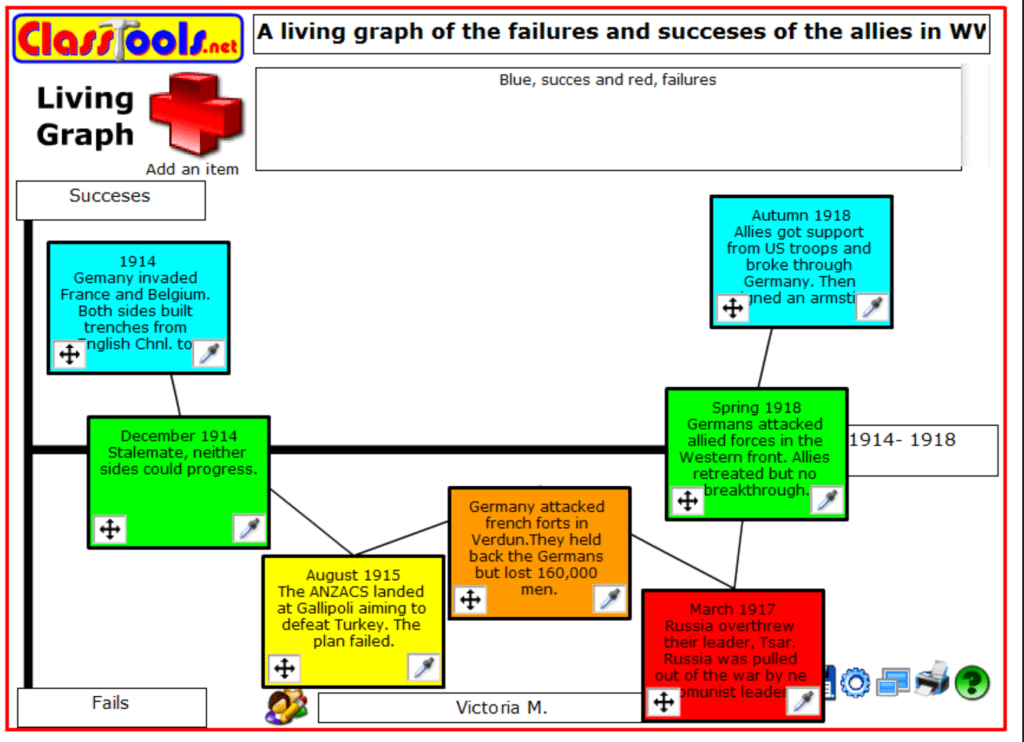

Vonnegut’s modelling of the shapes of stories seems to me to provide a clear visual representation of various narrative patterns or plot shapes, and to have a number of potential uses in history education. They might be used, for example, to provide a clear visual representation of the schematic narrative templates that Wertsch talks about (discussed in the previous post in this series) and to visually represent what Wertsch calls ‘specific stories’ (the narrative of a particular course of events). They could also be used to represent stories at a range of scales intermediate between those two extremes.

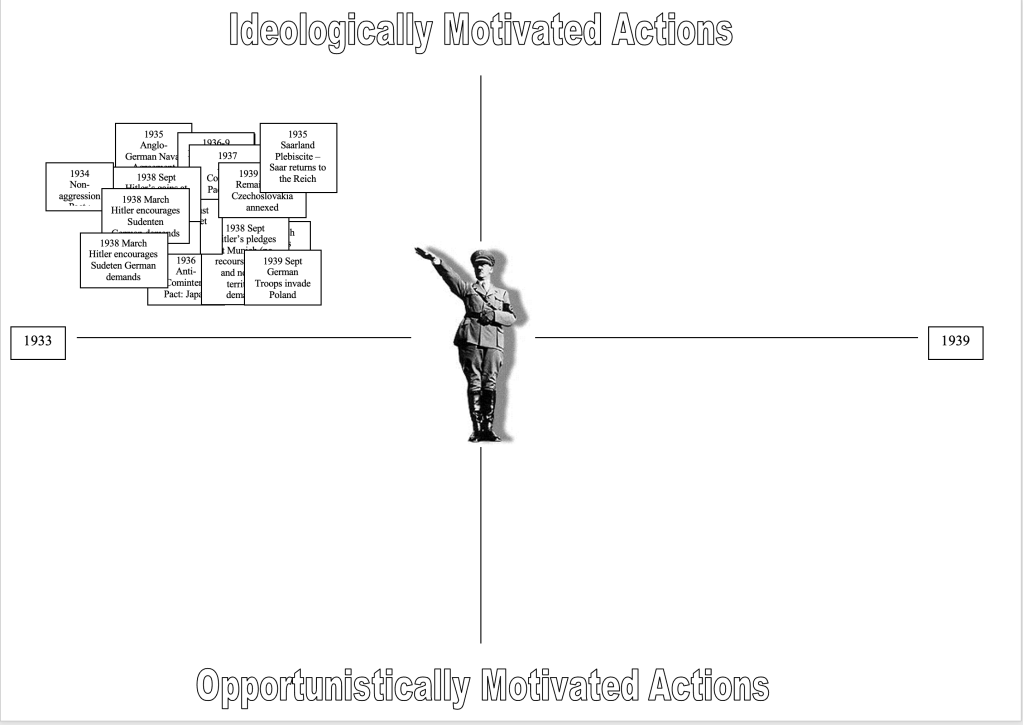

In fact, it seems pretty clear that they are already used in history education (as it were) in the form of ‘living graphs’ (discussed here at pps. 188/9), as is illustrated in the figure above, which has the same form as Vonnegut’s examples, and the figure below, which moves the vertical axis to the middle and which has a more precise analytical focus than a simple ‘good’ and ‘ill’ fortune focus that Vonnegut discusses. Clearly, the wheel can be invented at least twice.

The key point to note about Vonnegut’s story shapes is that, at least by 2004/5, he did not consider such plots ‘accurate representations of life’ but, rather, rhetorical devices to manipulate interest and attention, and to align with the expectations, of story-consumers. His contention is, first, that most of the stories in the Western narrative tradition trade in crude simplifications, and, second, that these simplifications are mis-leading.

Vonnegut’s Critique of Story Shapes

In elaborating his ‘shapes of stories’ Vonnegut was, I think, developing tools that lend themselves very readily to the work of what I’m calling narrative ethics. They are presented as devices to help us understand how stories work, and, therefore, how the storied-world in which we live works. Ought implies can, it has been said, and understanding how the world works is a precondition for acting in it effectively, for good or ill.

I think Vonnegut’s schemata have at least two other uses also, relating to ethical reflection on historical sense-making.(3)

First, these schemata draw attention to the evaluative work that is involved in all story telling. Up and down fluctuations are only possible if we have a clear axis and index on which we are measuring ‘rise’ and ‘fall’. Any notion of narrative development is normative, in some degree or other, if by development we mean anything more than simply ‘change.’ In drawing attention to the evaluative axis of stories, Vonnegut opens-up scope to interrogate and reflexively question those evaluations, a move we can follow and, perhaps, aim to open-up in our teaching, so as to encourage history students to become reflexive and critical thinkers about story.

Second, a line that rises and falls raises questions of it’s own. It implies stability of identity over time – it traces something through its ups and downs and, thus, posits a minumal core continuity in identity. How credible is that assumption, for example, in ‘national’ histories that posit ‘continuous’ national history over milennia, as the first ‘aim’ of the current English National Curriculum for History does? Furthermore, one might also ask questions about the singularity of focus that a single line of emplotment provides – is there really only one story that can and should be told? Whose story might that be? Who has the right to tell it, and what responsibilities arise from the activity of telling? If there is more than one story that could be told, who (if anyone) might have the right to chose which stories get prioritised and which marginalised or, even, erased?

Narration and Evaluation: surfacing narrative normativity

Vonnegut described himself as a ‘hack’ prior to the writing of Slaughterhouse 5 (Vonnegut, 2005: 18). He suggests that one of the reasons he wasn’t able to write his Dresden story in the years between his return home in 1945 and his final success in writing it 1968/9 was that he had been trying to write a story that conforrmed to false conventional expectations. He had been trying to tell the kind of Hollywood story in which ‘Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra and the others would play us’ (Vonnegut, 2005: 18). In effect, he could only write his Dresden book when he stopped trying to ‘hack’ it, abandoned the standard writerly tricks, and responded to Mary O’Hare’s request (discussed further in the post that follows this one) to ‘tell the truth for a change’ (Vonnegut, 2005: 19).

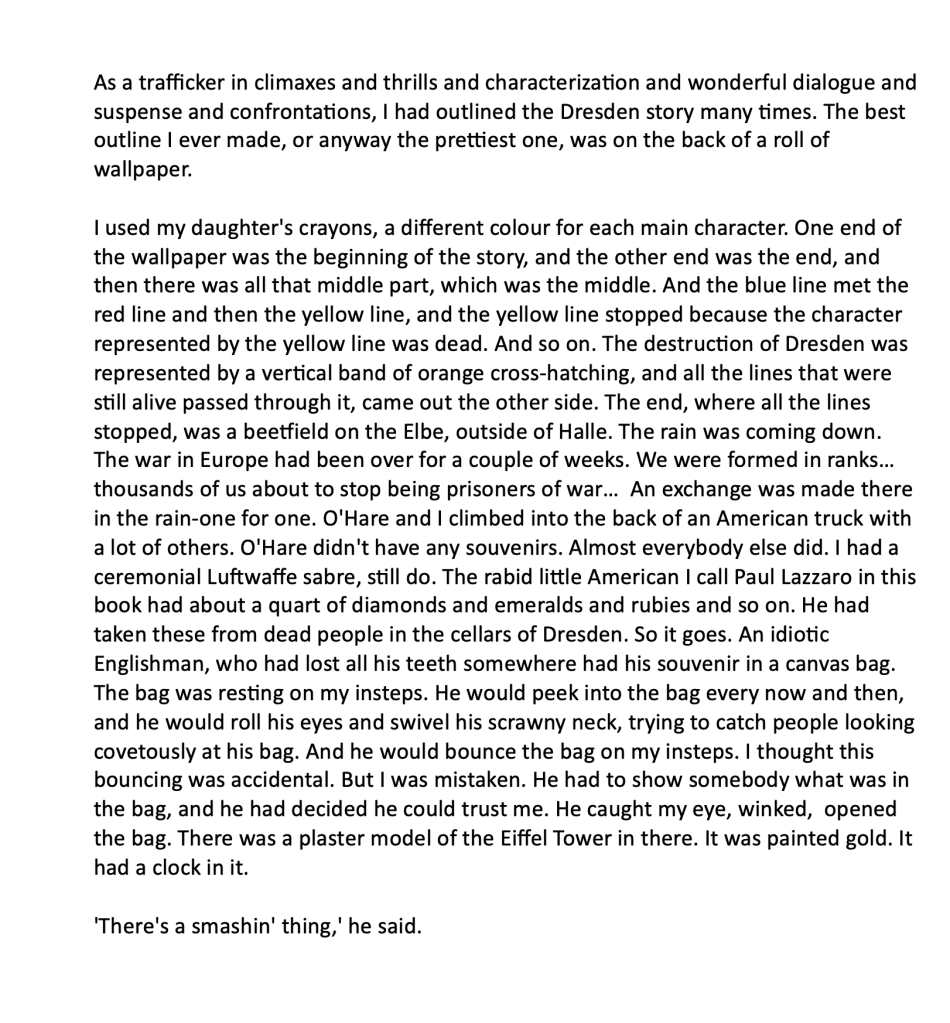

He talks, at one point in Slaughterhouse 5, about trying to apply his own story-graphing techniques in planning the story, and, I think, dramatises their failure.

The passage juxtaposes climax-generating story-plotting techniques with the entirely anticlimactic absurdity of a gold-painted plaster Eiffel Tower with a clock in it. After the hecatombs of Dresden, the firestorms and the ‘corpse-mining,’ represented by orange cross-hatching on his story schema, we come to an incongruous narrative non-sequeter: ‘an idiotic Englishman’ covertly hiding-sharing his garish model Eiffel Tower.

In his later ‘shape of story’ lecturers (in the 2004 lecture recording but not in the undated earlier version) and in his later write-ups of his insights (Vonnegut 2005 versus 1981), Vonnegut brings Hamlet into the picture. The point that he uses Hamlet to make is that in real art, rather than popular story-telling of the kind he had made a living from as a ‘hack,’ simple narrative patterns don’t work, because one of the things that art does is problematicise, rather than enact, simple evaluative schemes. In A Man Without A Country (2005), the Hamlet story schema diagram is, in effect, a schema without a narrative line, since it isn’t clear, as the story unfolds, whether a development in the story is ‘good news’ or ‘bad news.’ In other words: ‘Shakespeare told us the truth… The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is’ (2005: 37).

Billy Pilgrim (on the left in the image above), the largely fictional protagnonist of Slaughterhouse 5, is a passive anti-hero. He is without obvious character motivation. There is no ‘object’ that he ‘lacks’ and ‘seeks,’ of the kind that figure in work of narrative theory, such as Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale. He is not involved in any clear narrative drama or conflict – the agon that is needed to pitch pro- and ant-agonist against each other is entirely absent. He seems to almost entirely lack will and intention, also, and is content merely to enjoy ‘nice’ moments, and to enjoy them entirely as moments, without any driving narrative direction or expectation. He flits back and forth between moments, ‘unstuck in time’ (1969: 19) and, thus, free of any obvious narrative line.

As Tom Roston observes, in The Writer’s Crusade: Kurt Vonnetgut and The Many Lives of Slaughterhouse 5: ‘we can see that on Vonnegut’s fluctuations-in-ill-and-good-fortune chart, Pilgrim’s story has no curves. It starts very low and remains there all the way across. But it doesn’t feel that way reading the novel because Vonnegut shreds the sequences, reordering and connecting them with time-travelling threads’ (2021: 80). In his master work, then, Vonnegut very clearly tells us that it is an illusion to think that real stories have conventional shapes, and that we should be sceptical of the kinds of story that shape-up too easily, in nice perceptible plot lines, climaxes, and so on.

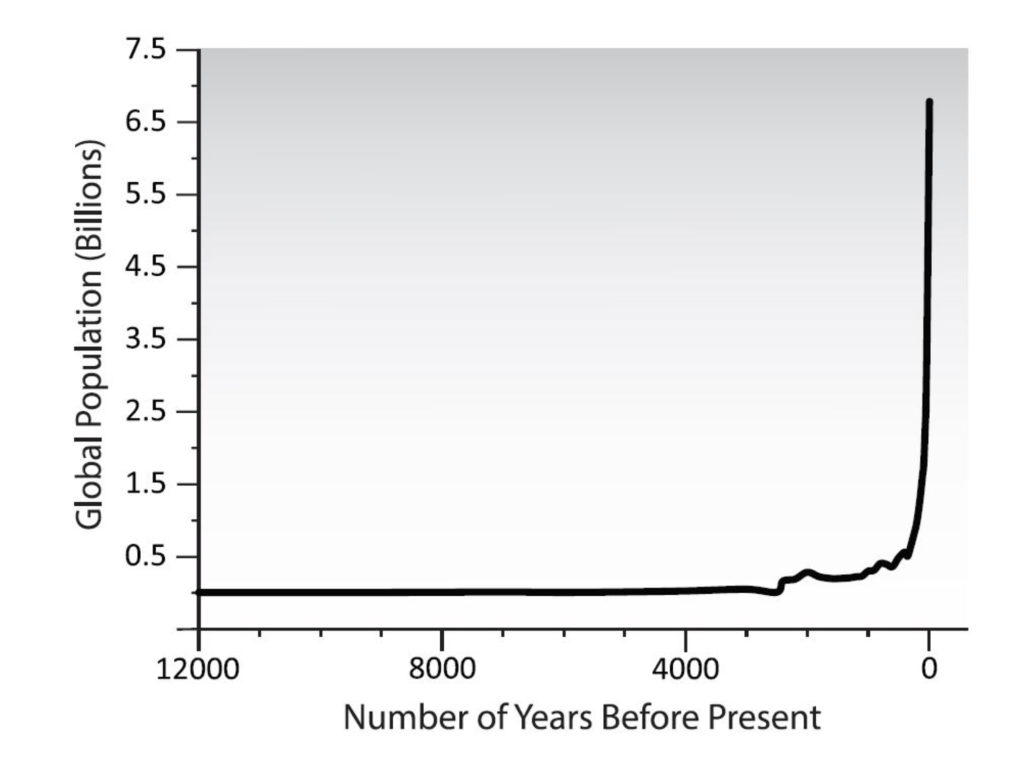

Whatever applies in Hamlet or Slaughterhouse 5, one might reply that none of this has application in history education where we can often be very clear about what we are trying to track over time, as in the world population graph above. It is true, of course, that the price of grain, the number of election riots, the reporting of violent assaults in Old Bailey Online, and innumerable other things, are questions where a graph can be unproblematically constructed – at least in principle, data-sets permitting. Nonetheless, as things like the debate on the ‘standard of living’ in the Industrial Revolution show, when evaluative judgments are involved – of the ‘This change is (or is not) an improvement’ kind – things get rather more complicated. Do we place more weight, in calculating standards of living, on food prices or on work-place autonomy, for example? Once we move beyond description, and into judgments, history inevitably becomes normative. And to handle normative judgments effectively, one has, first, to recognise them.

Toeing the Narrative Line: surfacing narrative exclusivity

To trace ‘rise and fall’ on a graph you have to have a line to follow – in other words, there must be a singular entity (‘Napoleon,’ ‘the Mensheviks,’ ‘the working class, ‘ and so on) whose fortunes you set out to trace and which itself remains stable, in at least some minimal sense, throughout the story. If ‘it’ is to have a ‘story’ unfolding in time, it must remain an ‘it’ for the duration of that unfolding.

Tracing the fortunes of such entities does at least two things, I think, that raise questions with ethical implications. First, the question ‘What do we see and what do we miss, if we focus excluively on X?’, and, second, the question ‘In what senses can we meaningfully claim that X remains the same entity over time?’

The first question takes us back to Brecht’s worker (discussed in the first blog in this series) and their objections to the kind of historical blindness that results from exclusive focus on the decisions and actions of one type of historical actor: ‘Caesar defeated the Gauls. Did he not even have a cook with him?’

Brecht’s worker does for history what Stoppard’s Rozencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead does for Hamlet, directing us to look at those the original narrator classified as bit-part players and supporting actors without a story line of their own worthy of attention, and directing us to frame a history around them instead of focusing on the canonical figure that story traditionally centres. This is also what both Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, and Auden’s commentary on it in his ‘Musée des Beaux Arts,’ do, directing attention away from Icarus crashing into the sea, a central focus in Ovid’s narrative in The Metamorphoses, and directing attention towards a ploughman, for whom that crash ‘was not an important failure’ (Auden, 1938).

As has already been noted in earlier blogs in this series, a key task for historiography – as for history education – in our time is to recentre narratives away from erstwhile ‘subjects’ of history and to look at the slienced pasts of those who these historical ‘subjects’ subjected to various kinds of oppression, both in historical reality and in narrative historiography. This is work that scholars like Edward Thompson and Michel-Rolph Trouillot pioneered and that contemporary history educational projects, such as Project LETHE or the work of Justice 2 History, are addressing.

The questions that using continuous subject labels for histories raise are not, perhaps, so frequently explored. Perhaps they ought to be? The English National Curriculum, as has been noted, makes the somewhat extraordinary move, in its opening aim, of claiming that the islands presently at least partly in the United Kingdom have a singular continuous history – a claim that ignores the plural existence of the four nations that are currently contituent of the United Kingdom state and the fact that each have their own separate histories and their own separate history curricula.

What this points to, I think, is the role that histories can play in shaping, in enabling and in erasing identities. One imagines that the phrase ‘understand the history of these islands as a coherent, chronological narrative’ was authored by an English politician, as ignorant of the differentiated histories of these islands and their constituent nations as the then Prime Minister John Major showed himself to be, in 1992, when he spoke of ‘1000 years of British history,’ ignoring the fact that the Act of Union was signed in 1707.

That presentist assumptions should project current identities back into the past and forward into the future is probably unsurprising. However, if history education is good for anything, it should serve, minimally, to remind people that ‘what is’ has not ‘ever been so,’ and that what seems normal and permanent today can readily pass into history. ‘Heaven smiles,’ Shelley wrote, ‘and faiths and empires gleam, like wrecks of a dissolving dream.’

It is also possible, of course, for presentist assumptions about institutions to inform actions that actively seek to transform and reshape futures, so that past fluidities and hybridities are erased. Something like this seemed to have been proposed, in 2022, when the Conservative former Brexit Minister Lord Frost argued that the government should change the world by changing how it talked, and by prioritising statehood (the UK) over nationhood (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland): “Somehow we have all drifted into speaking as if this country were already a confederation made up of four ‘nations’ that have chosen to work together (but could equally choose differently)… But the UK is a unitary state, not a federation or a confederation. Both the 1707 and 1801 Acts of Union fused the participants into one state in which all were equal, first ‘Great Britain’, then the ‘United Kingdom’, with one sovereign legal personality and one Parliament and government… if you are a citizen of that unitary state, you are British.”

A useful task, for historical research and for history education, perhaps, is to keep the entities posited in histories that trade in long-term continuities under constant review. What changes and what remains the same over time in these entitites, and what role do present discourses and practices play in maintaining, or even in helping to manufacture, such continuities? What role should historical writing and history education play in seeking to maintain, or to change, the narrative underpinnings of the worlds we currently inhabit?

*****

Endnotes

(1) I first read about these ideas in a remarkable 2014 blog post on Open Culture featuring powerfully Vonnegut-illuminating infographics by Maya Eilam. Eilam has developed an important ‘Narrative Practice‘ project, using Vonnegut and other resources to explore the question ‘What happens when we tell stories differently?’.

(2) Vonnegut states that he found that his shapes did not apply to what he calls ‘primitive’ people’s stories – their stories were ‘dead level, like the B-E’ axis (2005: 29). This is problematic language, of course, and much of Vonnegut’s ‘humour’ is often problematic (something that I will return to in a later post). Vonnegut is, I think, aiming to be ironic, however, in using the term ‘primitive’ here. His analysis contrasts the stories of Shakespeare and the Arapaho, both of which, he says, don’t map onto simplistic story shapes, with the erroneous and simple stories that he discusses using these shapes (2005: 28-29 and 37). In other words, he seeks to show the ‘primitive’ stories are more sophisticated than the thinking of the cultures that coined self-boosting developmental hierarchies and evaluative pseudo-scientific terms like ‘primitive.’

(3) There is more to be said about the practical-pedagogic (rather than the narrative-ethical) uses of Vonnegut’s story-schemata. I will post a shorter practical note on here shortly.

References

Vonnegut, K. (2005) ‘Here’s a Lesson in Creative Writing,’ in A Man Without Country: A memoir of life in George W. Bush’s America. (2007 Edition). London: Bloomsbury, pp.23-37.

Vonnegut, K. (2004) ‘Shape of Stories’ lecture, February 4th 2004. YouTube.

Vonnegut, K. (1981) Palm Sunday: An autobiograpical collage. 2021 Vintage Edition). London: Vintage.

Vonnegut, K. (1969) Slaughterhouse 5 or the Children’s Crusade: A duty dance with death. 1991 Vintage Edition. London: Vintage.

Vonnegut, K. (no date) ‘Shape of Stories’ lecture. YouTube.

Vonnegut, K. and McConnell, S. (2019) Pity The Reader: On Writing With Style. New York: Seven Stories Press, pp.201-215.