© The Trustees of the British Museum

One of the things I did on my second teaching practice, as a trainee teacher in Norwich in 1993, was teach Charles Dickens’ Hard Times (1854) to an English A Level Class. It was a privilege to do so, although I doubt I taught the novel well – my ‘main’ subject specialism was History and English was ‘subsidiary.’ I expect and hope that my class will have forgotten all about my teaching, but I hope at least some of them remember the novel.

I relished the prospect of teaching Dickens. I’d been entranced by Fagin, Bill Sykes and Nancy in Oliver! (1968) in the early 1970s and then by violent effigies like Wackford Squeers, in Dickens period TV drama in the late 1970s. I had studied Dickens’ Great Expectations and Little Dorrit in English Literature at school, and had read him for pleasure – although I read Hardy more. The Early Victorian period fascinated me as an undergraduate – its Chartists, utilitarians and utopian reformers. All of this coalesced in a kind of recognition and imagined home-coming when visiting my maternal grandmother’s home town, Hetton Le Hole, around the time of her funeral in 1988. Passing Primitive and Wesleyan Methodist chapels, old grocers’ shops, working men’s clubs felt like revisiting the scene of so many familiar dramas.

Finally, Hard Times had begun to impinge on my imagination during my teacher training when I began to be interested in the history of education and historic educational practices. The peculiarities of the Gradgrindian world view, modelled so closely on Jeremy Betham‘s ‘fiction’-busting, and the detail of the monitorial system of education both became very interesting in this context, as did the Victorian ‘object lesson‘ and a number of other matters relating to Victorian pedagogies, from the National Schools to John Ruskin.

I don’t remember much about my teaching of Hard Times – although I do remember that one student inferred that Stephen Blackpool was obsessed by money because he kept saying ‘mun’ (i.e. ‘must’). It looks – judging by my annotations to the text (e.g., below) – like I was particularly interested in questions of plot structure and homologies between narrative components and transformations – I was reading about Propp, early Barthes and Levi Strauss at the time, and mistook plot diagrams and matrices for narratology. As I read those annotations now, this was me trying (and not entirely managing) to work through the homology –

- Gradgrind : his daughter : : Jupe : his daugher

I revisited all of this last week, as I started reflecting on something that had stuck in my mind ever since I’d read Hard Times closely in order to teach it in 1993. This was the common reference to compasses in both Dickens Hard Times (1984: 184-5) and in Blake’s Ancient of Days (1794) and Newton (1795-c.1805), and what seemed to me at the time to be the common meanings attached to engaging with the world with compasses, geometry and associated forms of rationality. ‘Had Dickens read Blake?’ I wondered.

© David Olivier 2006 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

I had wondered this but I had never asked anyone who might have known the answer or done anything, myself, to research it. That could easily be done, I’m sure – there must be studies of Dickens’ probate records and scholars must have asked what books he owned and what he had read (at least one such enquiry turns-up rapidly online). All I knew – as I put it here last week – was that ‘Blake’s star only really rose once the pre-Raphaelites picked him up’ so it was unlikely that Dickens had read him, but that it was also true ‘Wordsworth knew him’ and that it was possible, therefore, that others were aware of his work, even, perhaps, in the 1840s and 50s.

The Blake/Dickens question occurred to me again last week, for the first time in a long time, perhaps because I had recently finished S.F. Said‘s marvellous – and marvellously Blakean – Tyger (2022). I asked English scholars I knew via Twitter the question, and, as a result, learned the following, thanks to the generous and erudite Adam Roberts.

As Roberts said, then, it seems very unlikely – although of course not impossible – that Dickens had ever seen – let alone been influenced by – Blake’s Newton or his Ancient of Days.

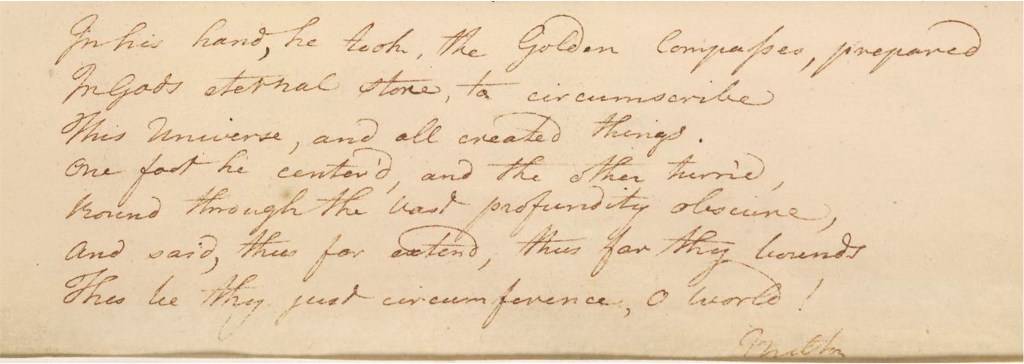

Where external breadcrumb trails aren’t available – such as – for the sake of argument – a record of a copy of Europe: A Prophecy in Dickens’ library records – we must rely on internal textual evidence, and there is a inscription under the British Museum’s copy of the Ancient of Days that looks, at first, to give us some internal evidence to work with (the inscription reproduced below). I spent some minutes comparing this and Dickens’ ‘compasses’ paragraph. There more I looked at the two, the more parallels began to appear and the more convinced I became, despite the facts of the matter, that the passages were linked.

However, on checking back with the British Museum’s online curatorial notes, it became clear that this text wasn’t in Blake’s hand but ‘annotated in pen in a near-contemporary hand, possibly of George Cumberland’ and, also, that the text wasn’t Blake’s text but ‘verses from Milton.’

In the end, then, I was asking the wrong question – in 1993 and again last week. The question should have been ‘We know that Blake read Milton – he wrote a prophecy all about him after all – had Dickens done so also and, if yes, was this where both of them picked-up the compass metaphor as a striking figure for ambitious and controlling intellect?’ What explains the parallels between Blake and Dickens here isn’t any direct textual link but the wider traditions and tropes of English poetry.

I had spotted the parallel but not the link. George Cumberland – if that’s whose handwriting that was – had seen both the parallel and the intertextual reference that explained it.